Gearing Up for Tevis Cup

By Paula Parisi October 6, 2011One hundred miles in 24 hours on horseback ― that’s the Western States Trail Foundation’s Tevis Cup endurance race. Riders who’ve made the trek from Lake Tahoe to Auburn describe it as an adrenaline-fueled test of strength, will and strategy that sees them trotting along narrow switchbacks edged by thousand-foot drops, climbing 50-degree inclines and crossing a trestle that spans 300-feet over the California River, 150-feet below.

Those taking part in the 56th iteration Oct. 8-9 will also face some new obstacles in the form of three hours of additional darkness, fresh snow and new rules for the starting order. No wonder only half the starters will make the finish line and receive the coveted Tevis belt buckle that signifies they’ve completed the race. (Editor’s note: Late on Oct. 6 the Tevis race was rerouted due to the harsh weather conditions.)

“It’s 100 miles of the toughest terrain you’ll ever ride,” said Janine Esler, who notches her eighth Tevis this year. “At the very beginning you climb from 6,500 feet to 9,000 feet in four miles. You’re riding over rocks, along cliffs and through bogs that sometimes come up to your horse’s belly. Imagine stepping-stairs, where horses have to leap up these huge boulders with water pouring down the sides. The environment is extreme.”

Concerns about light and clime are the result of the race being pushed from its original July 16 date, a bid to let the unseasonably late snow packs in California’s High Sierra melt. “July and August are the only times you’re guaranteed of not having bad weather up here,” said Esler, whose Esler Arabians is based in nearby Granite Bay. “It’s going to be slick and icy.” Days before the race there was snow –six inches!– at the starting line in Robie Park. Said WSTF boardmember and Tevis volunteer Terryl Reed: “It’s certainly going to be a different race this year!”

Although sunny skies and perfect riding temperatures of mid-60s to mid-70s are predicted for Saturday and Sunday, the mercury is expected to dip below 30 degrees at night. Since the Tevis riders depart at 5:15 a.m., they’re also going to have an extra 90 minutes of darkness at either end of the race. Some have expressed concern that particularly at the start of the race, with fresh horses that are trained to be competitive and “get out front,” the conditions are daunting.

“The horses will be so amped and animated, on a single-track trail. With potential icy sections and 200 competitors, I certainly will have my work cut out for me,” said one entrant, echoing thoughts shared by many, but adding “the Tevis Cup committee members have been working around the clock to make the trail as safe as possible, taking particular care with regard to the limited hours of light this year.”

Pack a Nightlight!

By night, riders can expect illumination courtesy of a waxing gibbous (slightly larger than half-sized) moon. Although Tevis is usually scheduled to coincide with a full moon, depending on cloud cover there have been some very dark rides. Esler described how racers light the trail with glow sticks attached to the horses’ breastplates. “You can’t use anything like a head-mounted light, because it blinds the horse. Horses actually see pretty well in the dark – much better than humans. My advice: if you trust your horse, don’t even try to steer in the really dark parts.”

Crockett Dumas, a Utah farmer who has completed five Tevis races, isn’t scared of the dark. “For me, the earlier the better. I’d ride at 4 a.m. if I could. We started the AERC (American Endurance Ride Conference) National Championship at 4, and it was really dark, but it was fine.” He completed that 100-mile race in approximately 12 hours, placing fourth overall at the August event in New Mexico.

Over rougher terrain, 2010 Tevis winners John Crandell and Heraldic finished in just under 15 hours, crossing the finish line at 10:15 p.m. By comparison, first-timer Lisa Ford finished the race in about 19 hours, placing ninth alongside her husband, Garrett, who finished eighth (his best effort in six tries). Garrett Ford, president and CEO of EasyCareInc. (maker of the Easyboot horseshoe) received the 2010 Haggin Cup for Best Conditioned Horse for The Fury.

Crandell, who also won Tevis with Heraldic in 2006, will not be among this year’s starters, opting instead for the Pan American Games Endurance Championship, Oct. 21-23 in Santo Domingo, Chile. To what extent will Crandell’s absence create room at the top? “Without a doubt, everyone that has entered the Tevis Cup 2011 has a better chance of winning because John and Heraldic will not be competing,” said Shannon Constanti, who finished second last year riding Crandell’s back-up horse, LR Bold Greyson. “John is an elite competitor. When he enters a ride, he brings a sound horse that has been conditioned to race at a winning pace. He thoroughly does his homework and is a very intelligent rider.”

Racing at Crandell’s side was invaluable to Constanti, providing “many hours of opportunity to watch and listen to his racing philosophy and strategy. He showed me how to ride the Tevis Cup trail at a winning pace, effortlessly and efficiently.” This year she’ll race Tallahassie’s Fire, a 13-year-old National Show Horse (half Arabian, half American Saddlebred) owned by farrier Tom Christofk. Constanti won two 50-milers on the horse, which makes its 100-mile debut at Tevis.

The importance of horse conditioning and a smart racing strategy cannot be overestimated in terms of finishing well at Tevis. “Every step has to be deliberate, because it’s a very technical ride,” Dumas said. “You have to be careful not to burn your horse out. Once you hit California Street, a 17-mile section about 65 miles in, you can really make some time, but if you’re outta horse, then it’s just a long, long ride.”

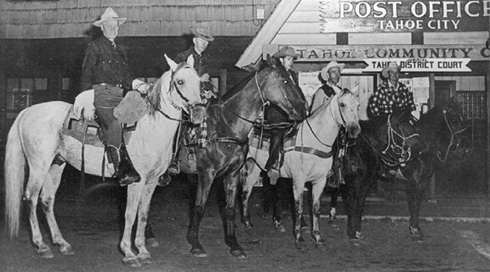

Riders at the first-ever Tevis Cup in 1955. On the gray horse at far left is Wendell Robie. (Photo courtesy Western States Trails Foundation)

What has become one of the most hotly contested equestrian competitions in the world started out as something of a lark. Tahoe local Wendell T. Robie devised a test to prove he owned the fittest, most forward horse in town: trekking from Lake Tahoe to Auburn in 24 hours. “Some friends went along for the ride, and they had a good time, so they did it again next year. That was the start of the modern sport of endurance racing,” said Phil Gardner, who is something of an unofficial historian for the WSTF. In 1959 Will Tevis donated the trophy and the “Tevis Cup” was officially born. While other 100-mile endurance races have emerged, Tevis still stands as the most extreme.

Ironically, it is also distinct in that the prerequisites for entry are not terribly strict: a rider need only have logged 300 lifetime miles ― a pittance! Lisa Ford, who considers herself a casual enthusiast, has logged 2,000 miles, and a serious competitor with multiple horses can rack 1,000 to 3,000 miles a year. The only requirements for the horses are that they are at least six years old, and “shod or wearing protective footwear.”

The result: a lot of not terribly experienced riders can saddle-up on green horses for Tevis! This year, Gardner estimates about 10% of the 200 starters are new to the race. Another observer puts the number at closer to 30% for “inexperienced riders” – including those who may have prior Tevis starts, but were withdrawn (“pulled”) by one of the 15 or so veterinarians who check the soundness of the horses at various points along the way. (Roughly half the riders who start Tevis don’t finish, and don’t get their “buckle.”) “The vets are there to protect the overzealous competitor,” said Reed, who is Constanti’s mother and often competes in races with her daughter. An active member of the community that keeps the non-profit Tevis event going, Reed has earned four buckles and “not missed a race since 1967,” participating as a volunteer when not competing. Asked about the level of horsemanship she’s seen over the years, Reed said, “People who now have 20 buckles, I remember looking at them at the start of a race and saying to myself, ‘They’re never going to finish!’ What I’ve learned is it’s amazing how well people can do if they apply themselves.”

Safety, she stressed, is the top priority, for the horse as well as the riders. Many horses wear heart monitors to track their pulse as they go. Dehydration is another big concern. “The vets look at all the parameters. If the pulse is good, they still might pull you if the horse looks off. The pull-rate is pretty high. We’ve tried everything we can think of to improve it, including starting the Tevis Educational Ride.” That 75-mile course over two days is designed to acclimate first-timers to Tevis, and Reed said “people who’ve participated in that, their chance of finishing goes way up.”

“A person who isn’t experienced with endurance isn’t going to win,” Gardner said, adding “someone who has completed two- to four 100-mile races, with a well-conditioned horse they have a shot.” This year, even without Crandell in the lineup, the competition is expected to be fierce. “There are a lot of really good riders coming in from the East Coast, and some excellent horsemen that for whatever reason had some bad luck last year but are trying again,” Ford said.

Start Me Up

Another twist this year’s contestants will have to deal with is a change in rules as to the starting order. There are three pens from which Tevis racers embark in groups of 60: Pen 1, the first to launch, is considered the most desirable. These riders have as much as a 45-minute jump on the rest (who get no accommodation at the finish line for their later start). And for those really intent on racing (as opposed to those who “just want to finish”), it means not having to elbow past the lollygaggers. At the earliest point at which the faster riders in the second and third pens will encounter the first movers, the trails are steep and as narrow as 18-24 inches.

This year, for the first time, riders were assigned to a pen on a “first come, first served” basis, as opposed to the prior year’s finish and the speed and athleticism of the horse and rider team. Insiders say this was done in a bid for democracy (there was always some complaining, and unsanctioned backroom trading), and also to encourage early registration. Since profits from the race go to trail maintenance – and maintaining 100 miles of trail ain’t cheap! ― the very existence of the event depends on cash flow, generated through donations, endowments and sponsorships in addition to entry fees (between $300 and $500, depending on when you enter and whether you’d like to have a buckle if you finish). Riders from overseas ― there are a handful attending from Japan, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa – automatically qualify for Pen 1.

In years past, Constanti and all top 10 finishers would have been guaranteed a Pen 1 departure, but this year she was not among the first 50 to register and wound up in Pen 2. “My preference would be to start in Pen 1 because I’m riding a horse that is just typically faster than other horses, whether it’s walking or trotting. I’m confident we’ll be quite competitive regardless of where we start the race. The distance of a very challenging 100 miles will sort out the lost time at the start. And a lengthy slow warm up, might just be the key to our success this year!”

Dumas agreed that strategy is more than half the battle of winning this race. “Last year, I was about 180th at the beginning, and I finished seventh. You can start out back and ride a smart race and do well. It’s a long, tough ride.” Dumas, who is 65, said the Tevis race “makes chopped liver out of me.” But you won’t hear him complaining. “All I want’s a map and a start time!” Miki Cohen, a 25-year endurance veteran who rode her first Tevis in 1986, said it took five tries before she got her buckle. She summarized: “Tevis is the hardest race, but also the best run and the most challenging. It’s not for wimps!”

Short URL: https://theequestriannews.com/?p=5284